Monday Accidents & Lessons Learned: Review of a Comprehensive Review

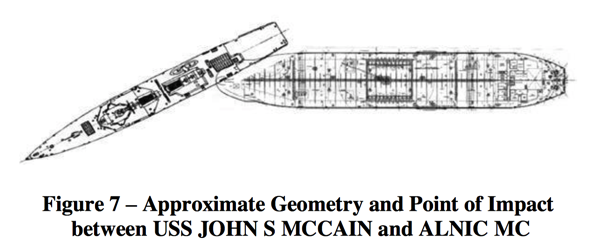

What will it take for the US Navy surface fleet (or at least the 7th Fleet) to stop crashing ships and killing sailors? That is the question that was supposed to be answered in the Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents. (See the reference HERE.) This article critiques the report that senior Navy officials produced that recommended changes to improve performance.

If you find yourself in a hole, stop digging!!

Will Rogers

The report starts with two and a half pages of how wonderful the US Navy is. The report then blames the crews for the accidents. The report stated:

“In each incident, there were fundamental failures to responsibly plan, prepare and execute ship activities to avoid undue operational risk. These ships failed as a team to use available information to build and sustain situational awareness on the Bridge and prevent hazardous conditions from developing. Moreover, leaders and teams failed as maritime professionals by not adhering to safe navigational practices.“

It also blamed the local command (the 7th Fleet) by saying:

“Further, the recent series of mishaps revealed weaknesses in the command structures in-place to oversee readiness and manage operational risk for forces forward deployed in Japan. In each of the four mishaps there were decisions at headquarters that stemmed from a culturally engrained “can do” attitude, and an unrecognized accumulation of risk that resulted in ships not ready to safely operate at sea.“

Now that we know that more senior brass, the CNO, the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of Defense, the Congress, or the President (current or past) have nothing to do with the condition of the Navy, we can go on to read about their analysis and fixes.

The report states that individual root cause analyses of US Navy crashes were meant to examine individual unit performance and did NOT consider:

- Management Systems (Doctrine, Organization, Leadership, Personnel)

- Facilities and Material

- Training and Education

The “Comprehensive Report” was designed to do a more in-depth analysis that considers the factors listed above. The report found weaknesses in all of the above areas and recommended improvements in:

- Fundamentals

- Teamwork

- Operational Safety

- Assessment

- Culture

The report states:

“The recommendations described in this report address the skills, knowledge, capabilities, and processes needed to correct the abnormal conditions found in these five areas, which led to an accumulation of risk in the Western Pacific. The pressure to meet rising operational demand over time caused Commanders, staff and crew to rationalize shortcuts under pressure. The mishap reports support the assertion that there was insufficient rigor in seeking and solving problems at three critical stages: during planning in anticipation of increased tasking, during practice/rehearsal for abnormal or emergency situations in the mishap ships, and in execution of the actual events. This is important, because it is at these stages where knowledge and skills are built and tested. Evidence of skill proficiency (on ships) and readiness problems (at headquarters) were missed, and over time, even normalized to the point that more time could be spent on operational missions. Headquarters were trying to manage the imbalance, and up to the point of the mishaps, the ships had been performing operationally with good outcomes, which ultimately reinforced the rightness of trusting past decisions. This rationalized the continued deviation from the sound training and maintenance practices that set the conditions for safe operations.“

The report mentions, but does not emphasize, what I believe to be a major problem:

“The findings in chapters four through eight and appendix 9.10 underscore the imbalance between the number of ships in the Navy today and the increasing number of operational missions assigned to them. The Navy can supply a finite amount of forces for operations from the combined force of ships operating from CONUS and based abroad; this finite supply is based both on the size of the force as well as the readiness funding available to man, train, equip and sustain that force. Headquarters are working to manage the imbalance. U.S. Navy ships homeported in the continental United States (CONUS) balance maintenance, training and availability for operations (deployments and/or surge); the Pacific Fleet is re-examining its ability to maintain this balance for ships based in Japan as well. Under the Budget Control Act of 2011 and extended Continuing Resolutions, the ability to supply forces to the full demand is – and will remain – limited.“

The report does not say how many more ships the 7th Fleet or the US Navy needs.

The report also stated:

“The risks that were taken in the Western Pacific accumulated over time, and did so insidiously. The dynamic environment normalized to the point where individuals and groups of individuals could no longer recognize that the processes in place to identify, communicate and assess readiness were no longer working at the ship and headquarters level.“

This could be used as a definition of normalization of deviation. To read more about this, see the article about Admiral Rickover’s philosophy of operational excellence and normalization of deviation by CLICKING HERE.

Normalization of deviation has been common in the US Navy, especially the surface fleet, with their “Git er Dun” attitude. But I’m now worried that the CNO (Chief of Naval Operation), who was trained as a Navy Nuke, might not remember Admiral Rickover’s lessons. I also worry that the submarine force, which has had its own series of accidents over the past decade, may take shortcuts with nuclear safety if the emphasis on mission accomplishment becomes preeminent and resources are squeezed by Washington bureaucrats.

The military has been in a constant state of warfare for at least 15 years. One might say that since the peacekeeping missions of the Clinton administration, the military has been “ridden hard and put up wet” every year since the mission started. This abuse can’t continue without further detrimental effects on readiness and performance in the field.

The report summary ends with:

“Going forward, the Navy must develop and formalize “firebreaks” into our force generation and employment systems to guard against a slide in standards. We must continue to build a culture – from the most junior Sailor to the most senior Commander – that values achieving and maintaining high operational and warfighting standards of performance. These standards must be manifest in our approach to the fundamentals, teamwork, operational safety, and assessment. These standards must be enforced in our equipment, our individuals, our unit teams, and our fleets. This Comprehensive Review aims to define the problems with specificity, and offers several general and specific recommendations to get started on making improvements to instilling those standards and strengthen that culture.“

This is the culture for reactor operations in the Nuclear Navy. But changing the culture in the surface fleet will be difficult, especially when any future accidents are analyzed using the same poor root cause analysis that the Navy has been applying since the days of sail.

After the summary, the report summarizes the blame-oriented root cause analysis that I have previously reviewed HERE, HERE, and HERE.

Another quote from the report that points out the flaws in the US Navy root cause analysis is:

“Leadership typically goes through several phases following a major mishap: ordering an operational pause or safety stand down; assembling a team to determine what happened and why; and developing a list of discrete actions for improvement. Causes are identified, meaningful actions taken, and there has been repeated near- term success in instilling improved performance. However, these improvements may only have marginal effect in the absence of programs and processes to ensure lessons are not forgotten. Still, all levels of command must evaluate the sufficiency of internal programs and processes to self-assess, trend problems, and develop and follow through on corrective actions in the wake of mishaps.”

Instead of thinking that the lessons from previous accidents have somehow been forgotten, a more reasonable conclusion is that the Navy really isn’t learning appropriate lessons and their root cause analysis and their corrective actions are ineffective. Of course, admitting this would mean that their current report is also, probably misguided (since the same approach is used). Therefore they can’t admit one of their basic problems, and this report’s corrective actions will also be short-lived and will probably fail.

The 33 people (a large board) performing the Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents were distinguished insiders. All had either previous military/DoD/government affiliations or had done contracting or speaking work for the Navy. I didn’t recognize any of the members as a root cause analysis expert. I didn’t see this review board as one that would “rock the boat” or significantly challenge the status quo. This isn’t to say that they are unintelligent or bad people. They are some of the best and brightest. But they are unlikely to be able to see the problems they are trying to diagnose because they created them, or at least they have been surrounded by the system for so long that they find it difficult to challenge the system.

The findings and recommendations in the report are hard to evaluate. Without a thorough, detailed, accurate root cause analysis of the four incidents that the report was based upon (plus the significant amount of interviews that were conducted with no details provided), it is hard to tell if the finding are just opinions and if the recommendations are agenda items that people on the review board wanted to get implemented. I certainly can’t tell if the recommended fixes will actually cause a culture change when that culture change may not be supported by senior leadership and congressional funding.

One more point that I noticed is that certain “hot button” morale issues were not mentioned. This could mean that certain factors affecting manning, training time wasted, and disciplinary issues aren’t being addressed. Even mentioning an example in this critique of the report seems risky in our very sensitive, politically correct culture. Those aboard ships know examples of the type of issues I’m referring to; therefore, I won’t go into more detail. If, however, certain issues won’t be discussed and directly addressed, the problems being created won’t be solved.

Finally, it was good to see references to human factors and fatigue in the report. Unfortunately, I don’t know if the board members actually understand the fundamentals of human performance.

For example, it seems that senior military leadership expects the Commanding Officer, the Officer of the Deck, or even the Junior Officer of the Deck to take bold, decisive action when faced with a crisis they have never experienced before and that they have never had training and practice in handling. Therefore, here is a simple piece of basic human factors theory:

If you expect people to take bold, decisive action when faced with a crisis,

you will frequently be disappointed. If you expect that sailors and officers

will have to act in crisis situations, they better be highly practiced

in what they need to do. In most cases, you would be much better off

spending time and energy avoiding putting people in a crisis situation.

My father was a fighter ace in World War II. One of the things he learned as he watched a majority of the young fighter pilots die in their first month or even first week of combat was that there was no substitute for experience in aerial combat. Certainly, early combat experience led to the death of some poor pilots or those who just couldn’t get the feel of leading an aircraft with their shots. But he also observed that inexperienced good pilots also fell victim to the more experienced Luftwaffe pilots. If a pilot could gain experience (proficiency), then their chances of surviving the next mission increased dramatically.

An undertrained, undermanned, fatigued crew is a recipe for disaster. Your best sailors will decide to leave the Navy rather than facing long hours with little thanks. Changing a couple of decades of neglect of our Navy will take more than the list of recommendations I read in the Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents. Until more ships and more sailors are supplied, the understaffed, undertrained, underappreciated, under-supported, limited surface force that we have today will be asked to do too much with too little.

That’s my critique of the Comprehensive Review. What lessons should we learn?

- You need to have advanced root cause analysis to learn from your experience. (See About TapRooT® for more information.)

- Blame is not the start of a performance improvement effort.

- Sometimes senior leaders really do believe that they can apply the same old answers and expect a different result. Who said that was the definition of insanity?

- If you can’t mention a problem, you can’t solve it.

- People in high-stress situations will often make mistakes, especially if they are fatigued and haven’t been properly trained. (And you shouldn’t blame them if they do … You put them there!)

- Just because you are in senior management, that doesn’t mean that you know how to find and fix the root causes of human performance problems. Few senior managers have had any formal training in doing this.

Once you have had a chance to review the report, leave your comments below.