The Blame Root Cause

Blame?

NTSB Accident Report on

USS John S. McCain Collision

• • •

Recently, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) published a marine accident report about the root causes of the collision of the USS John S. McCain and the Liberian flagged Alnic MC. The collision occurred on August 21, 2017.

As with any NTSB report, there was thorough evidence collection and a lot of information. But in this article, I want to focus on the Human Factors issue that the report highlights. We mentioned this issue in a previous blog article:

- Human Factors Issue in USS John S McCain Crash Not Specifically Identified in Navy Report (Nov 2017)

Next, we will discuss other potential root causes (including blame) and the Navy’s response (lessons learned).

Error Trap – Bad Human Factors

If the sailors controlling the ship’s steering (the Helmsman and Lee Helmsman) didn’t make a mistake when transferring propulsion control, this accident never would have happened. Let’s look at the issue and consider the root causes.

It should have been a simple task. After all, this was the Navy’s most advanced steering system. And steering a ship with the helm had been happening since the days of sail. Below is what the helm looked like when I was in the Navy…

And below is what it looks like when a previous Secretary of the Navy takes control of the helm on a U.S. Naval Academy patrol boat (note all the supervision for a very simple system … don’t want the SecNav to make a mistake)…

Below is what the “old” system looked like on the USS John S. McCain before it was replaced in 2016 (picture is not the McCain but is very similar)…

The Helmsman is on the left and the Lee Helmsman is on the right with an officer in between. The Helmsman steers the ship following orders from the Conning Officer (if stationed) or the Officer of the Deck. The Commanding Officer can always take control and give orders as well.

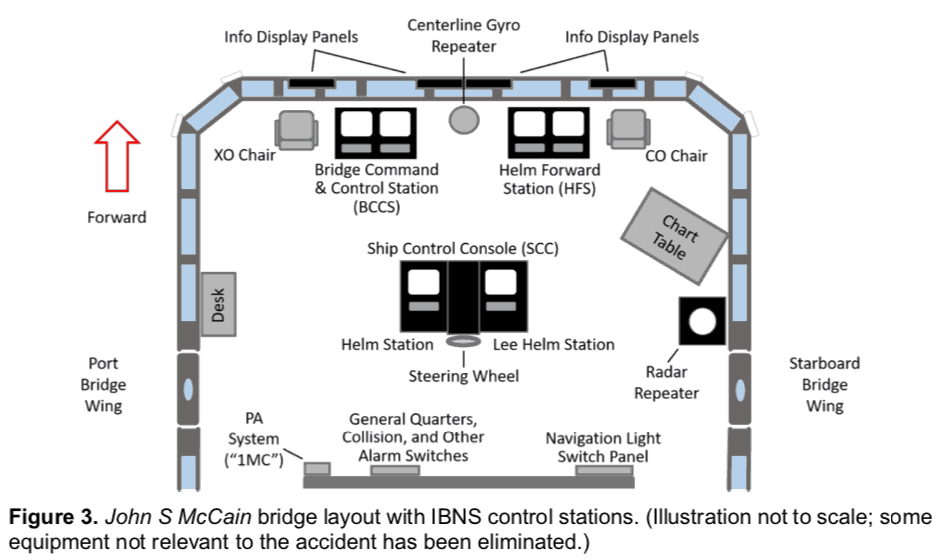

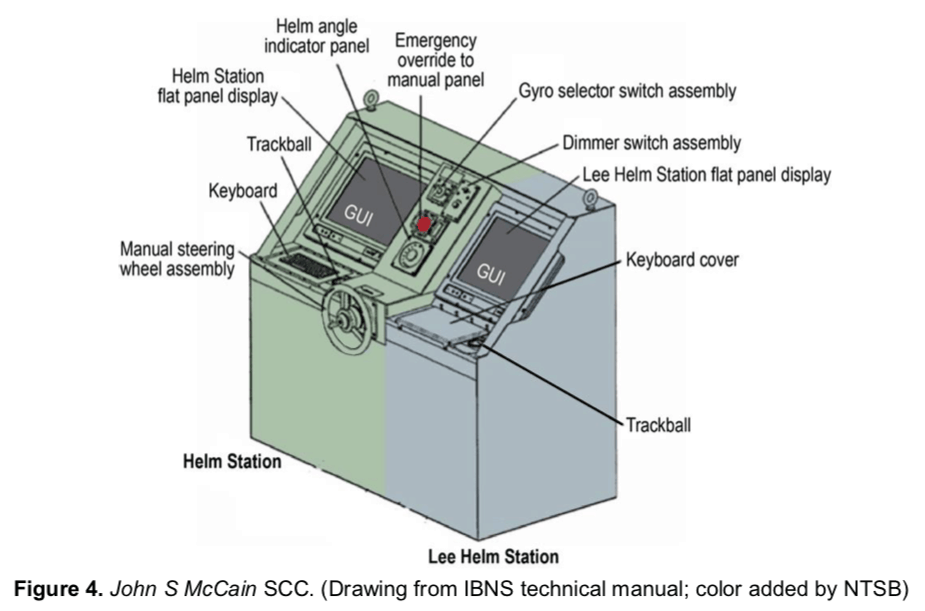

The old system above was replaced by a new, touchscreen-based system with a graphical user interface (GUI). The main control panel (helm) is located in the center of the bridge. See the drawing from the NTSB Report below…

The design should have been in compliance with the Department of Defense human factors standards. However, some of the system’s design did not meet the standards according to the NTSB. The part that was non-compliant controlled propulsion (the screws) and menus for transferring steering from one station to another.

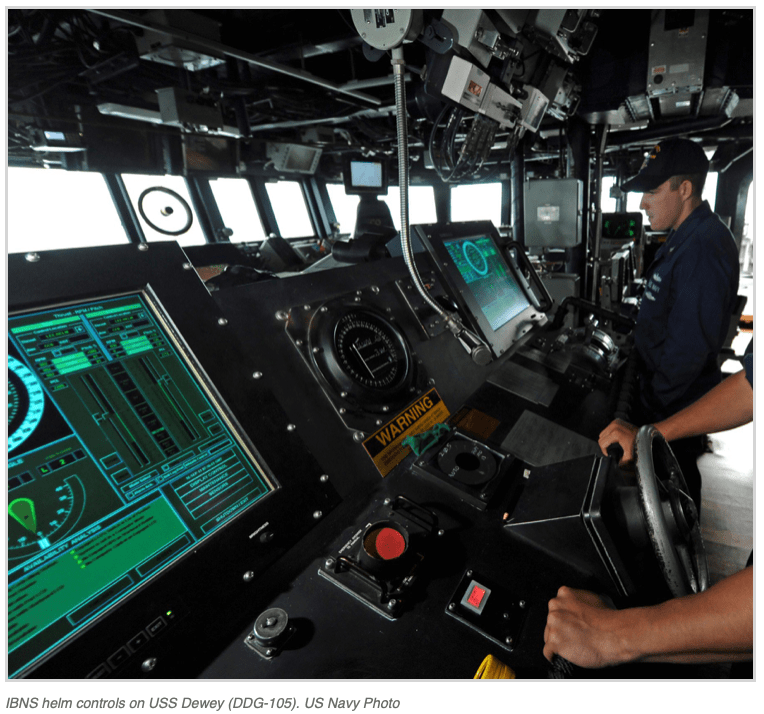

What did the new system look like? Like a video game. See the US Navy photo below…

You can see the Helmsman’s hands near the ship’s wheel and the Lee Helmsman to the right. The system is also shown in a drawing (below) from the NTSB report…

Thus, the “new” system was quite different from older, more manual systems.

The new system had five means of controling the steering with varying amounts of computer assistance and five different control panels to steer from. In addition, the propellers (often called screws) and engines of the ship could be controlled via the touchscreen and these controls had different modes and screens where they could be controlled via a menu.

There was a manual used by the crew to understand the system. But it didn’t cover all of the modes and all of the functions that were covered in the manufacturer’s technical manual (not available to the crew).

There was a key difference between the manual mode (the mode most similar to the old way of doing things) and the computer-aided mode. When in Manual Mode, steering could be transferred without the Helmsman’s permission. This became especially important when switching control of the helm (steering) and lee helm (propulsion control).

There was no procedure for shifting the helm (steering) or the lee helm (propulsion control) from one station to another. The operators (the Helmsmen) just knew how to do it from training (on the job training passed from one Helmsman to the next).

One of the features of the new helm controls is that a single person, the Helmsman, could control the helm and the lee helm from a single display. This reduced the number of people required to stand watch by one. This was important because the Navy was trying to cut staffing – an initiative that started in the late 1990s and continued all the way through the 2000s to 2010 (and perhaps to this day).

Simple Description of the Accident

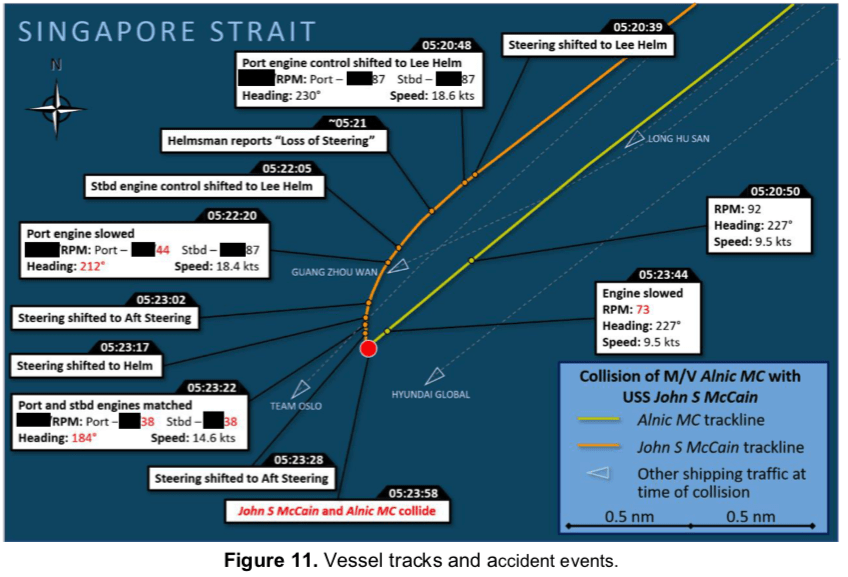

So what happened to cause the accident? The following happened in just 3 minutes.

The ship had entered the westbound Singapore shipping lanes and shipping (traffic) was getting busy. The special watchstanders to take the ship into port (the Sea & Anchor Detail) which included an experience Helmsman (called a Master Helmsman) and an experienced Lee Helmsman were due to take over the watch in about 15 minutes.

But this morning, a single Helmsman was in control of both steering and propulsion control. He had been standing watch since 1:45 AM and had no sleep prior to taking the watch. He was fatigued and ready for some rest. Another fairly inexperienced Helmsman came to relieve him at 5:30 so he could eat breakfast. The Commanding Officer (CO) decided that traffic was getting busy and that the off-going Helmsman should stay until the Sea & Anchor detail arrived (just 15 minutes) and he could be Lee Helm and control the propulsion until then. This would take some workload off the current Helmsman and set them up for turnover to the Sea & Anchor Detail. He told the Helmsman (just arrived) to transfer control of the lee helm (propulsion control) to the lee helm station.

What happened next started the chain of events that led to the accident. The details are provided in the NTSB report.

The Helm and Lee Helm goofed up and only transferred control of one shaft/screw (1/2 of propulsion) to the lee helm and accidentally transferred control of the helm (steering) to the lee helm. In their current mode of operation, this put the rudder amidships and, because of wind and current, the ship started a slow turn to port (turning left in front of a ship they had just passed).

The Helmsman realized he didn’t have control of the rudder and announced that he had “lost steering.” This started turmoil on the bridge as everyone focussed on the loss of steering casualty.

There was a procedure for a loss of steering and the first step was to hit the Emergency Override Button. However, the Helmsman thought that the button transferred control to aft steering (where the rudders were powered by hydraulic rams). The other enlisted watchstanders thought the same (that is what they were trained to believe). The Officer of the Deck thought that steering was in Manual Mode (which it was on the helm station – but was not on the lee helm station) and that hitting the button just put the steering in Manual Mode. Therefore, she thought they could skip that step in the procedure (it was already complete). Therefore, the button was not pressed. However, the bridge team followed the remaining steps in the procedure which didn’t solve the problem.

In the meantime, the Lee Helm noticed that he only had control of one shaft/screw. He reached over to the helm station and completed the transfer of the remaining shaft/screw to his station (the lee helm). He did this improperly. When the Commanding Officer ordered speed slowed, the lee helm thought he was slowing both shafts/screws but only slowed the port shaft. This caused the ship to turn to more to port (in front of the oncoming ship), and caused the ship’s speed to slow.

By this point, there was almost no way to recover. In aft steering, the people arrived and the Commanding Officer ordered steering transferred to aft steering. In aft steering, they hit a button to do this but they had the rudder position 30° to port. This caused the turn to start to be even worse. But it didn’t last long or have much effect.

Why? Because just at that moment, the Helmsman hit the Emergency Override Button because he thought that sent control of the rudder to aft steering. Instead, it returned control of the rudder to the helm control station in manual mode.

The Helmsman then realized he had regained steering and announced it to the bridge watch team. The Commanding Officer ordered hard right rudder and the Helmsman put the rudder over hard right and the rudder started to move. But before the rudder had much effect, the McCain was struck by the Alnic MC.

The graphic below from the NTSB report shows the accident…

Classic Human Factors Accident

In my view, this accident was a classic human factors accident. An inexperienced, fatigued watchstander and another inexperienced watchstander made mistakes using a fairly complex computer-aided, touchscreen interface.

The old system was mainly knobs and dials. Fairly simple to use and understand. The new system was like a video game without instructions. What should have been a simple action became a disaster caused by human error.

In the TapRooT® System, human errors would be taken through the Root Cause Tree®. No doubt, the analyst would find:

- Human Engineering – Human-Machine Interface – Controls Need Improvement, and

- Human Engineering – Human-Machine Interface – Displays Need Improvement

To stop this type of accident, one can focus on stopping the initial error. That means that the displays and controls for the steering system (helm and lee helm) need to be changed. The NTSB recommended this.

Recently, the Navy decided that changing the system was a good idea. Rear Admiral Bill Galinis talked to the press and said the computerized steering system on the USS John S. McCain was a problem. The Navy would be replacing it with an older design.

What about the new, touchscreen, GUI interface steering and throttle control system? The Admiral said:

“…just because you can doesn’t mean you should…”

Also, the Navy is warning ships with this system to not use it in Manual Mode because of the risk of steering accidentally being shifted to a different station without requiring the permission of the Helmsman.

Other Root Causes

Were there other root causes besides Human Engineering ones? Sure. There were problems with:

- fatigue

- training

- communications

- work direction

- procedures

- management systems

But we won’t go into the details of these now.

But what about BLAME? Should the Commanding Officer and other crew members be blamed for this accident?

Was the Navy correct in taking disciplinary action against the Commanding Officer and crew members?

The Blame Root Cause

The USS John S. McCain was one of two accidents that happened in the Western Pacific. The other was the collision of the USS Fitzgerald with the MV ACX Crystal. The almost immediate action of the U.S. Navy was to relieve the Commanding Officers. In addition, the Navy decided to punish them. This resulted in a court-martial of both officers.

Why were they court-martialed? Perhaps it was because there were:

- Seven dead due to USS Fitzgerald collisions

- Ten dead due to USS John S. McCain collision.

In the Navy culture, someone had to be blamed (held accountable).

Is this really necessary?

And will those who were really responsible learn?

- Those who had led efforts to cut staffing?

- Those who had pushed for computerized systems so that manning could be reduced?

- Those who cut the Navy’s budget and ships but gave them ever-increasing missions at sea?

Will Lessons Be Learned?

Will the senior leadership of the U.S. Navy learn a lesson from this collision?

Will they stop economizing while taking on more operational commitments?

Will they fix the ship systems, train the sailors, and adequately staff the ships?

Will they start learning from past experience, audits, and assessments and insist on advanced root cause analysis to find human factors root causes (which weren’t reported in the Navy’s investigation)?

Will they “undo” the discipline that they have already handed out now that they know that a bad human factors design was the cause (or at least a cause, and I would say a main cause) of the USS John S. McCain collision?

The lack of formal training when the steering system was updated cannot be overlooked here as a major causal factor. While that has been noted within the Navy, a ship that is currently getting the steering/helm system modification at this time is still being tasked to go to sea without formal training and documentation on the system. A “tech rep” from private industry comes aboard to provide training but that is a far cry from formal training and documentation.

I cannot imagine a scenario where you would want multiple people to throttle different engines on a ship. My dad flew multi-engine planes in the Air Force and he handled the throttles on all the engines by himself.

In a generic sense, this is not a new issue – humans have been blamed wrongly for deficiencies rooted in the engineering of human-automation interaction, and for management decisions overly-influenced by cost/budget-cutting, delivery schedules, and other factors which should have been subservient to SAFETY. The Boeing 737 MAX is another example with parallels (e.g., all the information about the behavior of the automation, esp. in mode-switching not being fully disclosed to the human operators).