Decisions That Get People Killed

What causes major accidents?

You have probably heard some statistics that approximately 90% of major accidents are due to human error. And because we all believe that “To err is human,” this statistic makes sense.

We also become conditioned to blaming people at the “pointy end of the stick”. The people who touched something last.

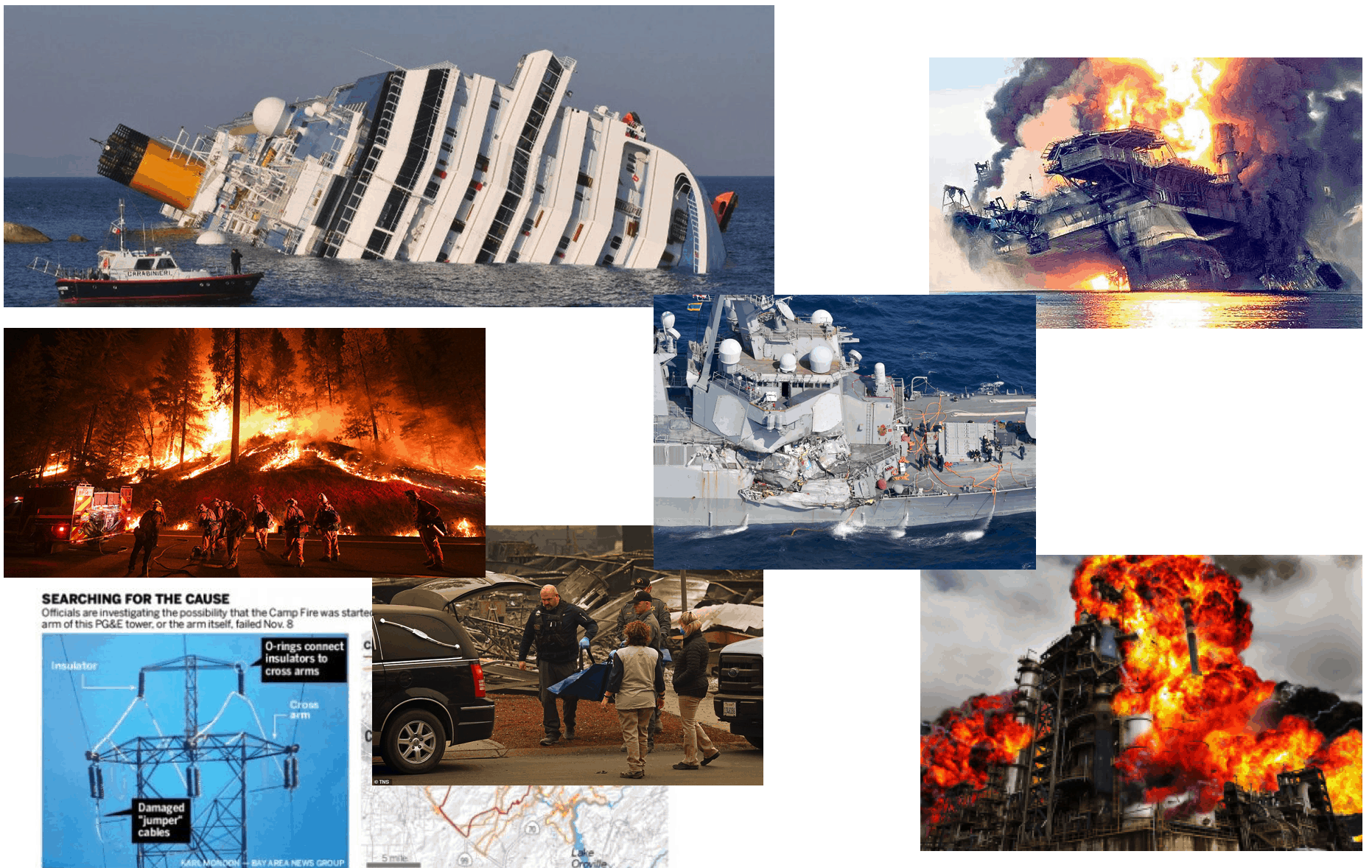

Look at the examples below. Isn’t the first question … “Who is the idiot!”

So when we talk about mistakes and accidents, who is really responsible?

Look at the list in the picture below. Who do you see that is blamed most often…

I would suggest that management – especially senior management – should place more emphasis on their actions that lead to major accidents.

I propose that senior management’s actions initiate most major accidents. Their actions set the ball rolling. They create the company’s culture. They influence middle managers and the line workforce’s actions.

Crossed Purposes

One of the major influences that cause accidents is senior management having crossed purposes.

They see quarterly earning goals as separate from safety, quality, and reliability.

The result? People become so focused on cutting costs and meeting quarterly goals that they take safety shortcuts that lead to major accidents.

Crossed Purposes Example

Let’s look at a single example of crossed purposed and the results – the Deepwater Horizon accident. (There are many more examples, but this one should do for the purposes of illustration.)

Soon after the Deepwater Horizon accident, I sought information on Tony Hayward’s management initiatives. I found a video by the British press praising his “no dry holes” initiative.

A video (which shortly thereafter disappeared from YouTube) said that Hayward had initiated a policy where BP would no longer accept a “dry hole.” Every well BP drilled would produce oil. The video implied that this policy had a major impact (for the better) on BP’s profitability.

This initiative by CEO Hayward was on top of the BP cost-cutting initiatives ingrained in the BP culture by Hayward’s predecessor, Lord Browne.

Thus, the engineers (ashore and offshore) were completely in line with senior management expectations when they erred toward completing the Macondo well and doing it as cheaply as possible. When one looks at the series of decisions made by BP’s engineers and company men, they accepted the risk to cut costs time after time.

Eventually, these decisions (that were in line with management’s “no dry holes” and cost-cutting initiatives) led to 11 fatalities and one of the most expensive accidents ever (latest estimates are over $65 billion).

But if you read BP’s incident report or watch their report video, you would never know this.

They don’t talk about senior management’s creation of a culture where decisions almost exclusively favor cutting costs over safety. Instead, their investigation is focused on the actions and decisions of those at the “pointy end” of the stick.

For example, the BP analysis of the cement job didn’t mention that insufficient time was allowed for the cement to cure. Thus, no matter how good or bad the cement choice was, it was doomed to fail because it was not allowed to cure properly. Cutting the time for the cement to cure cut costs.

Wouldn’t the investigation need to look at management’s impact on performance and safety to meet BP’s stated investigation goal of “making sure this accident could never happen again”?

Because senior management’s decisions were not examined in BP’s investigation, the crossed purposes of “no dry holes” and cost-cutting were never examined in the internal investigation.

What is the main question of this article?

So here is the main question of this article:

“What needs to happen at the senior management

level to prevent major accidents?”

Senior management’s vision and purpose must be aligned. A short version of what senior management needs to do to assure safety and high reliability while achieving quarterly goals is:

- Adopt and encourage an improvement vision. (See THIS BOOK to learn more.)

- Understand and adopt Rickover’s high-reliability organization principles.

- Adopt performance improvement best practices.

No Blame Vision

First, the Vision that management adopts and promotes cannot be the vision of blame or crisis management. They must adopt the improvement vision. To read more about these three visions, see:

That’s not all…

Second, senior management needs to understand and adopt the engineering and operational philosophies of Admiral Rickover. To learn more about his philosophies, read this series of articles:

Third, senior management needs to ensure that performance improvement best practices are implemented and encouraged. What are these best practices?

- Using TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis for Major Accidents

- Using TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis for Precursor Incidents

- Using TapRooT® Root Cause Analysis to Proactively Prevent Problems

- Using Advanced Trending Techniques to Spot Generic Issues

- Management Commitment to Improvement

What are the results?

What can be achieved when vision and purposes are aligned? This is my favorite quote about the Nuclear Navy’s performance:

We would love to work with you and your senior management to align your vision, purposes, and best practices to achieve outstanding performance. If you are interested, drop Mark Paradies a note by CLICKING HERE or calling 865-539-2139.

(This article is based on a talk given at the

2019 Global TapRooT® Summit by Mark Paradies.)

Not a comment, just a question.

Why did you only select (process)?

What is missing?

Are you talking about the Nuke Navy quote? If that is it, I would say that the Nuke Navy did not have the best industrial safety record. They didn’t melt down reactors (process safety) but they did have lost time injuries (industrial safety).