Normalization of Excellence – The Rickover Legacy – Facing the Facts

Third Part of Rickover’s Philosophy – Facing the Facts

In the past two weeks, we’ve discussed two of the “essential” (Rickover’s word) elements for reactor (process) safety excellence …

This week we will discuss the third, and perhaps most important, essential element:

FACING THE FACTS

What is facing the facts? Here are some excerpts of how Rickover described it:

“… To resist the human inclination to hope that things will work out,

despite evidence or suspicions to the contrary.“

“If conditions require it, you must face the facts and brutally make needed changes

despite significant costs and schedule delays. … The person in charge must

personally set the example in this area and require his subordinates to do likewise.“

Examples of Facing the Facts

Let me give two examples from Rickover’s days of leading the Navy Nuclear Power Program that illustrate what he meant (and how he lived out this essential element).

The Nautilus Steam Piping Replacement

Many people reading this probably do not remember the Cold War or the Space Race with the USSR. But there was a heated competition with national importance in the area of technology during the Cold War. This technology race extended to the development of nuclear power to power ships and submarines.

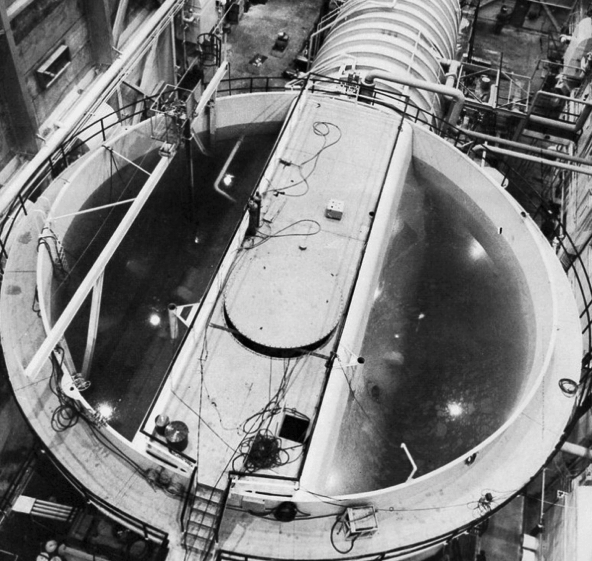

Rickover in 1947, Rickover proposed to the Chief of Naval Operations that he would develop nuclear power for submarine propulsion. The technical hurdles were impressive. Developing the first nuclear-powered ship was probably more difficult than the moon shot that happened two decades later. Remember, there were no computers. Slide rules were used for calculations. New metals had to be created. And new physics and radiation protection had to be created. None the less, Rickover decided that before he built the first nuclear-powered submarine, he would build a working prototype of the submarine exactly like the actual submarine that was proposed. It would be built inside a hull and surrounded by a water tank to absorb radiation from the reactor.

This first submarine reactor was built near Idaho Falls, Idaho, and went critical for the first time in March, 1953. Just imagine trying to do something like that today. From concept to critical operations in just 6 years!

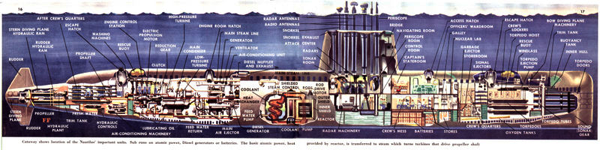

The prototype was then operated to get experience with the new technology and to train the initial crew of the first submarine, the USS Nautilus. The construction of the ship started in 1952 before the prototype was completed. Therefore, much of the construction of the Nautilus was complete before appreciable experience could be gained with the prototype. Part of the reason for this was that the lessons learned from the construction of the prototype allowed the Nautilus construction to progress much faster than was possible for the prototype.

However, during the operation of the prototype, it was found that some of the piping used for the non-reactor part of the steam plant was improper. It was eroding much faster than expected. This could eventually lead to a hazardous release of non-radioactive steam into the engineering space – a serious personnel hazard.

This news was bad enough, but the problem also had an impact on the Nautilus. There was no non-destructive test that could be performed to determine if the right quality piping had been used in the construction of the submarine. Some said, “Go ahead with construction. We can change out the piping of the Nautilus after the first period underway and still beat the Russians to sea on nuclear power.”

Rickover wouldn’t hear of it. He insisted that the right way to do it was to replace the piping, even though it meant a significant schedule delay. Accepting the possibility of poor-quality steel would be sending the wrong message … the message that taking shortcuts with safety was OK. Therefore, he insisted that all the steam piping be replaced with steel of known quality before the initial criticality of the reactor. He set the standard for facing the facts. (By the way, they still beat the Russians to sea and won the race.)

Radiation Exposure

The second example is perhaps even more astounding.

Since no civilian or Navy power plants existed, there were no standards for how much occupational exposure to radiation a nuclear technician could receive. In addition, submarines were made for war, and some proposed that any civilian radiation allowance should be relaxed for military men because they were sailors who must take additional risks. (Remember, we were doing above-ground nuclear weapons testing in the US and marching troops to ground zero after the blast during this period.)

Rickover’s staff argued that a standard slightly higher than the one being developed for civilian workers would be OK for sailors. This higher standard would save considerable shielding weight and would result in a faster, more capable submarine.

Rickover would hear nothing of it. He asked people to imagine that their son would be working on the ship. Would they want him to get a greater dose of radiation? He insisted that the shielding be built so that the projected radiation dose received by any sailor from the reactor during operation be no higher than that experienced by the general public. (Everyone receives a certain amount of exposure from solar radiation, dental and medical X-rays, and background radiation from naturally occurring radionuclides.) That was the design standard he set.

Many years later, it was noticed that Russian submarine crews were given time off after their deployments to relax in Black Sea resorts. Some thought this was just a reward for highly skilled sailors. However, it was later discovered that this time off was required to allow the sailors time for their bone marrow to regenerate after damage due to high levels of radiation. The Russians had not used extra shielding, and hence their sailors got significant radiation doses. Perhaps that is why Russian nuclear submarine duty got the nickname of “babyless duty.”

There was no similar problem for US Nuclear Power Program personnel. Rickover made sure that the facts were faced early in the design process and that no adverse health effects were experienced by US submarine sailors.

Does Your Company Face the Facts?

Let’s compare Rickover’s facing the facts to industrial practices. What happens when a refinery experiences problems and faces a shutdown? Does management “face the facts” and accept the downtime to make sure that everything is safe? Or do they try to apply bandages while the process is kept running to avoid losing valuable production? What would be the right answer to “face the facts” and achieve process safety excellence?

Have we seen major accidents caused by just this kind of failure to face the facts? You betcha!

Read On – Additional Elements of Rickover’s Philosophy

That’s the first three (and most important) of Rickover’s essential elements for reactor (process) safety excellence. But that isn’t all. In his testimony to Congress, he outlined additional specific elements that completed his reactor safety management system.

Read Part 6: Normalization of Excellence – The Rickover Legacy – 18 Other Elements of Rickover’s Approach to Process Safety

Very excellent article, a must read for every leader of any industry. Sadly, there are industries out there that still, even though professing to a “safety first” culture, put cost and schedule ahead of worker safety. This transcends onto site supervision, who then communicate urgency to the craft, ultimately paying the price, sometimes with their lives.